Food Chains and Food Webs and Their Role in Ecosystem Balance.

The intricate dance of life on Earth is choreographed by fundamental ecological principles, none more central than the concepts of food chains and food webs. These interconnected systems describe the pathways through which energy and nutrients flow, dictating the survival and prosperity of all living organisms within an ecosystem. Far from being mere academic constructs, food chains and webs are the very architecture of ecological balance, underpinning the stability, resilience, and biodiversity of our planet's diverse environments. Understanding their mechanics and the delicate equilibrium they maintain is paramount to appreciating the profound interdependence of nature and the critical role each species plays in the grand tapestry of life.

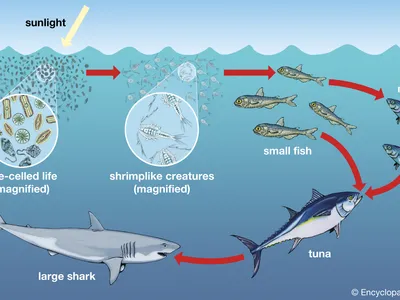

Food Chains: The Linear Foundation of Energy TransferAt its most basic, a food chain illustrates a linear sequence of organisms, each consuming the one below it to obtain energy and nutrients [1]. This progression defines distinct trophic levels, which categorize organisms based on their position in the feeding hierarchy relative to the initial energy source, typically sunlight [1][2]. The foundation of every food chain is occupied by producers (autotrophs), such as plants, algae, and some bacteria, which convert solar energy into organic compounds through photosynthesis [1][3]. In rare cases, like deep-sea hydrothermal vents, producers may utilize chemosynthesis. Moving up the chain, consumers (heterotrophs) acquire energy by ingesting other organisms [3]. These are subdivided into: primary consumers (herbivores), which feed directly on producers (e.g., rabbits eating plants) [1]; secondary consumers, which prey on primary consumers (e.g., foxes eating rabbits) [4]; tertiary consumers, which consume secondary consumers (e.g., eagles eating foxes) [4]; and in some longer chains, quaternary consumers. At the apex of these chains are apex predators, organisms not typically preyed upon by others [2]. Finally, decomposers, including bacteria, fungi, and detritivores like earthworms, break down dead organic matter from all trophic levels, recycling essential nutrients back into the ecosystem for producers to reuse, thus completing the cycle [3].

A crucial aspect of food chains is the unidirectional flow of energy and its inherent inefficiency [1][5]. Energy enters the ecosystem, primarily from the sun, and is transferred from one trophic level to the next, but not without significant loss [6]. The 10% rule in ecology states that, on average, only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is successfully transferred to the next higher level [7][8]. The remaining 90% is expended through metabolic processes (such as respiration, movement, and maintaining body temperature), lost as heat, or remains in undigested biomass that is not consumed [7][8]. This dramatic energy reduction at each step explains why food chains are typically short, rarely exceeding four or five trophic levels, as there simply isn't enough energy to support viable populations at higher levels [5][9]. This energy distribution is often visualized through ecological pyramids, which depict the decreasing amounts of energy, biomass, or numbers of organisms at successive trophic levels, with the broadest base representing producers and the narrowest top representing apex predators [4][9].

Food Webs: Complexity and InterconnectednessWhile a food chain offers a simplified, linear depiction of energy transfer, a food web provides a far more accurate and complex representation of feeding relationships within an ecosystem [1][10]. Instead of isolated sequences, a food web is a vast network of interconnected food chains, illustrating that most organisms have diverse diets and are often consumed by multiple predators [3][10]. This intricate web reflects the reality that an organism can occupy different trophic levels depending on its diet; for instance, humans can be primary consumers when eating plants, secondary consumers when eating herbivores like cows, and tertiary consumers when consuming predatory fish [4]. The presence of omnivores, which feed on both plants and animals, further enhances the complexity and connectivity of food webs [10].

The inherent complexity of food webs is not merely an aesthetic feature but a cornerstone of ecosystem stability and resilience [11][12]. A highly interconnected food web possesses functional redundancy, meaning that if one species declines or disappears, other species can often fill its ecological role or provide alternative food sources for predators [11][12]. This redundancy acts as a buffer against disturbances, preventing a complete collapse of the ecosystem [11][12]. For example, if a particular herbivore population decreases, its predators might switch to another abundant prey species, thus maintaining their own population and preventing an unchecked increase in other herbivores [12]. This adaptability is crucial for an ecosystem's ability to recover from environmental changes or the loss of a single species [11][13]. Furthermore, the concept of keystone species highlights how certain organisms, despite their potentially low abundance, exert a disproportionately large influence on the structure and function of an ecosystem's food web [14][15]. A classic example is the sea otter in kelp forest ecosystems. Sea otters prey on sea urchins, which in turn graze on kelp. Without sea otters, urchin populations can explode, leading to the overgrazing and destruction of vast kelp forests, which serve as critical habitats for numerous other marine species [15][16]. The removal of such a keystone species can trigger a trophic cascade, dramatically altering the entire ecosystem [17][18].

Role in Ecosystem Balance and ResilienceThe elaborate architecture of food webs plays a pivotal role in maintaining the delicate balance and resilience of ecosystems, orchestrating vital ecological processes that sustain life. One of the most critical functions is population control, achieved through dynamic predator-prey relationships [19]. Predators regulate the populations of their prey, preventing any single species from overpopulating and depleting shared resources [19][20]. This "top-down control" is balanced by "bottom-up control," where the availability of primary producers limits the populations of herbivores, which then limits carnivores [16]. The reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s serves as a powerful real-world example of this dynamic. Before their reintroduction, elk populations had boomed, leading to overgrazing of riparian vegetation. The return of wolves reduced elk numbers and altered their grazing patterns, allowing willow and aspen trees to recover, which in turn stabilized riverbanks, improved habitats for beavers and fish, and increased overall biodiversity [16][20]. This demonstrates how apex predators can trigger positive trophic cascades that restore ecosystem health [17][19].

Beyond population dynamics, food webs are indispensable for nutrient cycling, the continuous movement of essential chemical elements through living organisms and the physical environment [21][22]. Decomposers, the unsung heroes of the ecosystem, are central to this process [3][23]. By breaking down dead plants, animals, and waste products, they release vital nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus back into the soil and water [21][22]. These recycled nutrients then become available for uptake by producers, fueling new growth and restarting the cycle [3][21]. This continuous recycling, unlike the unidirectional flow of energy, ensures that finite resources are perpetually reused, maintaining the fertility and productivity of ecosystems [22][23]. A diverse community of decomposers, including bacteria, fungi, and various invertebrates, ensures efficient nutrient processing, contributing directly to ecosystem health and agricultural productivity [23][24]. The overall biodiversity within a food web enhances its stability by providing multiple pathways for energy and nutrient flow, making the ecosystem more robust against environmental fluctuations and species loss [11][25].

Threats to Food Web Stability and ConclusionDespite their inherent resilience, food chains and food webs are increasingly vulnerable to human-induced disturbances, leading to profound ecological imbalances. Habitat destruction and fragmentation, driven by deforestation, urbanization, and agriculture, directly eliminate species' homes and food sources, severing critical links within food webs [26]. Pollution introduces harmful substances that can have devastating effects. Bioaccumulation occurs when toxins, such as heavy metals (e.g., mercury) or persistent organic pollutants (POPs like DDT and PCBs), build up in an individual organism faster than they can be excreted [27][28]. These accumulated toxins then undergo biomagnification as they move up the food chain, becoming increasingly concentrated at higher trophic levels [27][29]. Apex predators, such as orcas or large predatory fish, can accumulate dangerously high levels of these substances, leading to reproductive failure, immune suppression, and mortality, as evidenced by DDT's impact on raptors or mercury in marine mammals [27][30].

The introduction of invasive species can disrupt established food webs by outcompeting native species, preying on them, or altering habitats, often leading to declines in native populations and shifts in ecological dynamics [19]. Climate change poses a multifaceted threat, altering species distributions, phenological events (like breeding and migration timings), and metabolic rates [31][32]. Rising temperatures can force species to move to cooler regions, creating mismatches between predators and prey or disrupting vital plant-pollinator relationships [31][33]. For instance, melting Arctic sea ice impacts the entire polar food web, affecting everything from phytoplankton to polar bears [26][31]. Finally, overexploitation, such as overfishing or overhunting, can decimate populations of key species, removing essential links and triggering trophic cascades with far-reaching consequences [17][19]. The decline of sea otters due to hunting, leading to sea urchin explosions and kelp forest destruction, is a stark example of such a cascade [19][34]. These disruptions underscore that the health of food webs is intrinsically linked to the overall health of our planet. Protecting these intricate networks, fostering biodiversity, and mitigating human impacts are not merely environmental goals but essential endeavors for securing the stability of ecosystems and, by extension, the well-being of humanity.