Human Life in the Paleolithic Era: Hunting, Gathering, and Nomadism.

The Paleolithic Era, an immense span of human history stretching from approximately 2.6 million years ago to about 10,000 BCE, represents the foundational chapter of human existence. During this Old Stone Age, our ancestors, from early hominins like Homo habilis and Homo erectus to anatomically modern Homo sapiens, forged a way of life intrinsically linked to hunting, gathering, and nomadism. This tripartite existence was not merely a survival strategy but a powerful crucible that shaped human biology, cognition, social structures, and technological innovation, laying the groundwork for all subsequent human development. This period, encompassing over 90% of human history, saw humans adapt to diverse environments across the globe, developing complex survival mechanisms that allowed them to thrive amidst challenging conditions [1][2]. Understanding this era requires delving into the intricate interplay of these core activities, recognizing their profound impact on human evolution and adaptation across varied global landscapes.

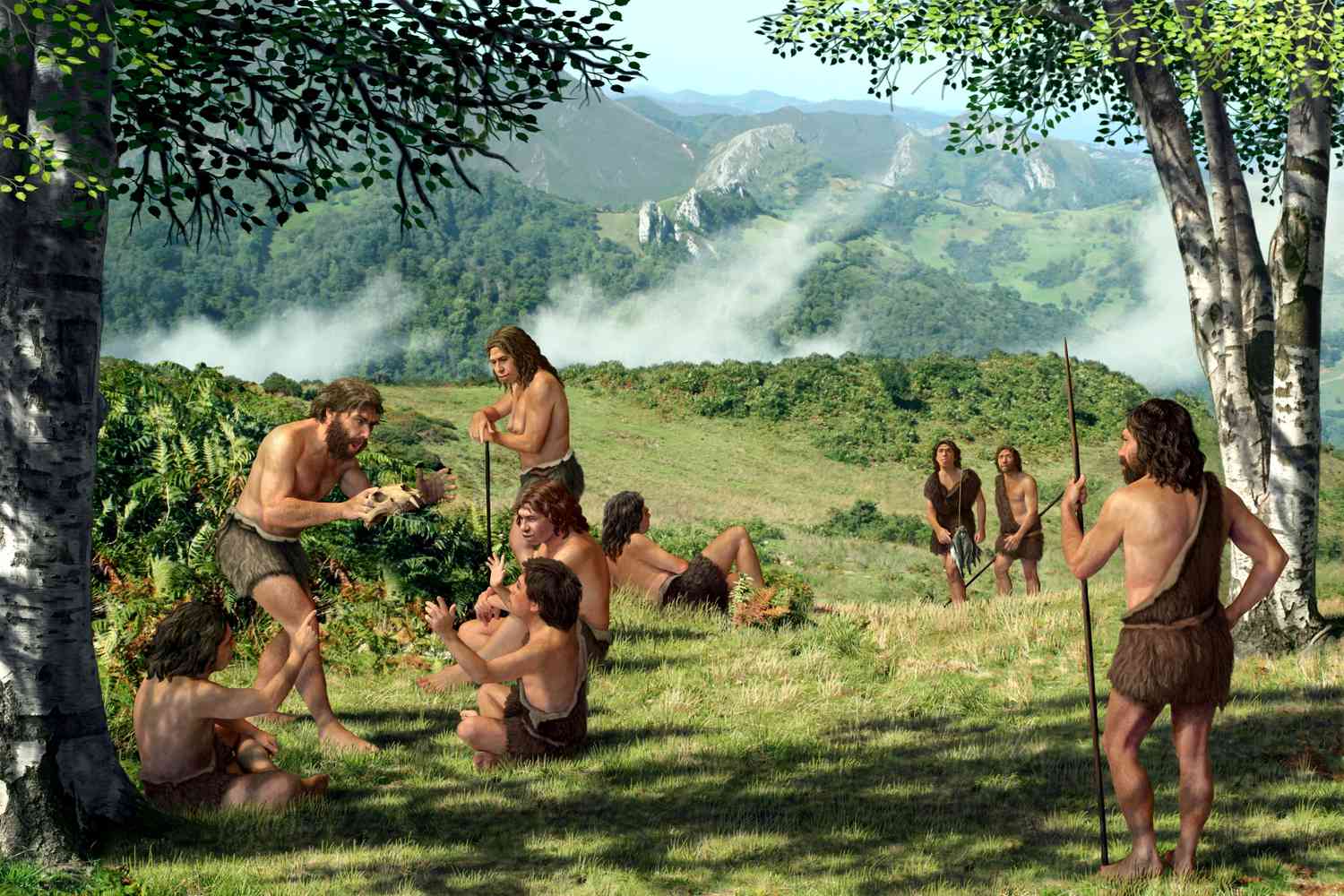

The Art and Science of Paleolithic HuntingHunting in the Paleolithic Era was far more than a simple act of killing; it was a complex endeavor demanding sophisticated intelligence, intricate social cooperation, and a continuously evolving toolkit. Early hominins likely scavenged and hunted smaller prey, with evidence suggesting early humans in the Lower Paleolithic scavenged carcasses rather than actively hunting large animals [1][2]. However, by the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, large game hunting became a defining characteristic, particularly for Homo sapiens and Neanderthals [3]. The evolution of hunting tools reflects this increasing sophistication. From the rudimentary Oldowan choppers, used for butchering and bone marrow extraction, to the versatile Acheulean handaxes, suitable for a myriad of tasks, the technological leap was significant. The Middle Paleolithic saw the widespread use of the prepared-core technique, which allowed for the creation of more controlled and consistent flakes, leading to stone-tipped spears—the earliest composite tools [3]. The Upper Paleolithic witnessed a revolutionary diversification, including the invention of projectile weapons like the atlatl (spear-thrower) and later the bow and arrow, along with specialized tools such as fishing nets, hooks, and bone harpoons around 90,000 years ago, which brought fish into human diets and provided a hedge against starvation [2][3]. Cooperative hunting strategies, evidenced by archaeological findings, underscore the advanced planning and communication required, with groups sometimes working together to kill large bison [4]. The successful pursuit of megafauna like mammoths necessitated a profound understanding of animal behavior, terrain, and weather patterns, fostering cognitive development in spatial reasoning, memory, and strategic foresight. The protein and fat derived from successful hunts were critical for brain development and sustaining energy levels in challenging environments, profoundly influencing human biological and intellectual evolution [5].

The Sustaining Bounty of Paleolithic GatheringWhile hunting often captures the imagination, gathering was the consistent bedrock of the Paleolithic diet, providing a reliable and often more abundant food source. Paleolithic peoples possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of their local flora, understanding which plants were edible, medicinal, or poisonous, and their seasonal availability [6][7]. Their diet was remarkably diverse, encompassing wild fruits, berries, nuts, seeds, roots, tubers, leaves, fungi, and honey [3][6]. Archaeological findings, such as starch grains on grinding stones and dental calculus, reveal the consumption of wild cereals and legumes long before the advent of agriculture [8][9]. For instance, microfossils from Neanderthal dental calculus show consumption of date palms, legumes, and seeds, with many exhibiting chemical changes consistent with cooking [6]. Recent studies focusing on charred plant remains from sites like Franchthi Cave in Greece and Shanidar Cave in Iraq indicate that human knowledge of edible plants and complex culinary preparation, including soaking, crushing, and cooking to remove toxic or unpalatable components, dates back at least 70,000 years, challenging the stereotype of ancient people only eating raw ingredients [8][10]. This deep botanical knowledge was critical for survival and likely passed down through generations. The division of labor, while not absolute, often saw women playing a primary role in gathering, foraging closer to temporary camps while men engaged in more distant hunting expeditions [11]. This specialization meant that gathering provided a stable caloric intake, mitigating the inherent risks and unpredictability of hunting [6]. Beyond food, gathered resources included materials for tools, shelter, clothing, and medicine, demonstrating an intimate knowledge of their environment [7]. This intimate relationship with the natural world fostered a profound ecological awareness, promoting sustainable foraging practices that ensured the long-term viability of their food sources.

The Imperative of Paleolithic NomadismNomadism was not a choice but an ecological imperative for Paleolithic humans, a dynamic response to the scattered and seasonal distribution of resources across vast landscapes [7][12]. Hunter-gatherers could not rely on a fixed food supply in one location; their movements were dictated by the migration patterns of animal herds, the ripening cycles of wild plants, and the availability of water and shelter [7][12]. This constant mobility meant that Paleolithic groups, typically small bands ranging from a few dozen to around 60 individuals, maintained a light material culture, carrying only what was essential and easily transportable [1][12]. This lack of accumulated material wealth is a key factor in the widely accepted theory of Paleolithic egalitarianism, where social hierarchies were minimal, and resources were often shared to ensure group survival [1][13]. Temporary shelters, ranging from natural caves and rock overhangs to constructed huts made of branches, animal hides, and mammoth bones, were characteristic of their transient lifestyle [1][7]. The need to move frequently also spurred innovation in transportable technologies and efficient resource utilization, with environmental awareness influencing their choice of raw materials for tools and shelters [7]. Furthermore, nomadism facilitated genetic exchange and the spread of ideas and innovations across vast geographical areas, contributing to the resilience and adaptability of human populations [14][15]. This constant movement fostered a profound spatial awareness and an intimate understanding of extensive territories, enabling groups to navigate complex landscapes and exploit a wide array of ecological niches. The nomadic lifestyle, therefore, was not merely about movement but about a sophisticated, adaptive strategy that allowed humans to thrive in a world without permanent settlements or agriculture, a mode of subsistence that occupied at least 90% of human prehistory [1][2].

ConclusionThe Paleolithic Era, characterized by the interdependent pillars of hunting, gathering, and nomadism, represents the crucible in which humanity was forged. These fundamental activities were not isolated practices but components of a holistic survival strategy that drove biological, cognitive, and social evolution. The demands of cooperative hunting fostered complex communication and strategic thinking, leading to advancements in tool technology and hunting techniques [3][16]. The meticulous art of gathering cultivated an encyclopedic knowledge of the natural world, revealing a diverse diet that included processed and cooked plant foods long before agriculture [8][10]. And the imperative of nomadism shaped social structures, technological innovation, and an unparalleled adaptability to diverse environments, fostering largely egalitarian societies due to the challenges of accumulating wealth [1][7]. This era, far from being primitive, was a period of profound ingenuity, resilience, and deep ecological understanding. The legacy of our Paleolithic ancestors endures in our genetic makeup, our cognitive capacities, and the very foundations of human sociality, reminding us that for millions of years, human life was a testament to dynamic adaptation and an intimate, respectful relationship with the natural world.