Rock Art and Cave Paintings: Expressions of Early Humans.

Rock art and cave paintings stand as profound testaments to the dawn of human creativity, offering an unparalleled window into the minds, cultures, and daily lives of our earliest ancestors. Far from mere decorative markings, these ancient artworks, etched and painted onto stone surfaces across every habitable continent, represent sophisticated expressions of symbolic thought, spiritual beliefs, and observational prowess. They challenge long-held notions about the cognitive capabilities of prehistoric hominins, including Neanderthals, and underscore art's fundamental role in human evolution. By examining their diverse forms, intricate techniques, geographical spread, and enduring mysteries, we gain invaluable insights into the complex tapestry of early human existence and the universal impulse to create and communicate across millennia.

A Global Tapestry of Ancient Art: Chronology and DistributionThe geographical and chronological scope of rock art is vast, revealing a global phenomenon that spans tens of thousands of years and multiple hominin species. While European cave art, particularly from sites like Lascaux and Altamira, has long captured public imagination, recent discoveries have significantly expanded our understanding of its origins and distribution. In Spain, non-figurative cave art, including hand stencils and red dots found in caves such as La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Ardales, has been reliably dated to over 64,000 years ago. This astonishing age predates the arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe by more than 20,000 years, providing compelling evidence that Neanderthals were capable of symbolic thought and artistic expression, challenging their long-held "dim caveman" stereotype. [1][2] Further reinforcing this, engravings in France's La Roche-Cotard cave, created by dragging fingers across soft clay walls, have been dated to between 57,000 and 75,000 years ago, also attributed to Neanderthals. [3][4]

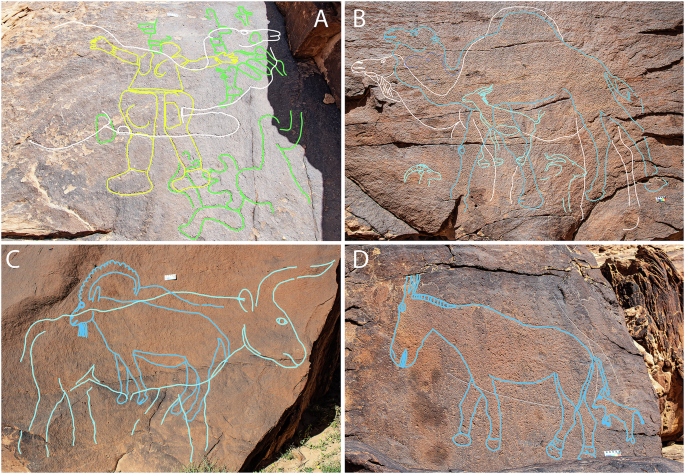

Beyond Europe, some of the oldest known figurative art hails from Sulawesi, Indonesia. Paintings depicting a warty pig have been dated to at least 45,500 years ago, making it the earliest known figurative depiction of an animal. [5][6] Even more remarkably, narrative cave art from Leang Karampuang in Sulawesi, portraying human-like figures interacting with a wild pig, has been dated to at least 51,200 years ago, representing the oldest reliably dated narrative art globally. [7][8] These Indonesian sites, along with a 73,000-year-old abstract cross-hatch design on a rock fragment from Blombos Cave in South Africa, demonstrate that artistic endeavors were not confined to a single region or species but were a widespread characteristic of early human behavior. [9] Other significant concentrations of rock art are found in Australia's Kakadu National Park, with some works dating back 20,000 years, and the vast rock art galleries of Tassili n'Ajjer in Algeria, documenting millennia of environmental and cultural change. [10][11] This global distribution underscores art as an intrinsic and early component of human cognitive and cultural development.

Techniques, Materials, and the Creative ProcessThe creation of rock art was a sophisticated endeavor, demanding ingenuity, resourcefulness, and a deep understanding of natural materials. Early artists meticulously sourced and prepared their pigments from the environment. Red and yellow hues were typically derived from various iron oxides, such as ochre, while blacks came from charcoal or manganese dioxide. [12][13] These raw materials were finely ground, often using harder stones, and then mixed with binders to create workable paints. Common binders included water, urine, animal blood, plant juices, egg yolk, or saliva, which helped the pigments adhere to the rock surfaces. [13] The application methods were equally varied and skilled. Artists used their fingers, brushes fashioned from animal hair or plant fibers, or even blew pigments through hollow bones or reeds to create stenciled effects, most famously seen in the numerous handprints found in caves worldwide. [12][13]

For petroglyphs, artists employed sharp tools made of flint or other hard stones to incise, scratch, peck, or sculpt designs directly into the rock. In some cases, on softer cave walls, even fingers were used to create intricate patterns. [13] A remarkable aspect of this creative process was the artists' ability to integrate the natural contours and textures of the rock surface into their compositions, giving a three-dimensional quality to their figures. [13] In deeper, darker sections of caves, where natural light could not penetrate, early humans utilized animal fat lamps for illumination, allowing them to work in challenging environments. [14] The flickering light from these lamps may have also animated the painted figures, creating a dynamic visual experience that could have been part of ritualistic performances. [14] This advanced technical mastery, combined with an aesthetic sensibility, demonstrates a profound level of cognitive ability and artistic intent, far beyond simple mark-making.

Unveiling Meaning: Themes, Interpretations, and Cognitive SignificanceThe themes depicted in rock art are rich and varied, yet certain motifs recur across diverse geographical and chronological contexts. Animals, particularly large wild species such as bison, horses, reindeer, mammoths, and aurochs, dominate many cave paintings, often rendered with remarkable anatomical accuracy and a sense of movement. [15][16] Human figures are less common and often more stylized or abstract, appearing as isolated heads, genitalia, or the ubiquitous hand stencils. Abstract symbols, including dots, lines, and geometric patterns, are also prevalent, their meanings largely enigmatic. [13][15] The purpose behind these creations remains a subject of intense academic debate, as the absence of written records necessitates inferential interpretation.

One prominent theory is "hunting magic," suggesting that depicting animals was a ritualistic act aimed at ensuring successful hunts or promoting animal fertility, a belief potentially reinforced by spear marks found on some painted figures. [17] Another compelling interpretation links rock art to shamanism, proposing that the artworks were created by shamans during trance states, perhaps to connect with the spirit world or to depict visionary experiences. The placement of many artworks in deep, inaccessible cave sections supports the idea of a sacred or ritualistic context, rather than mere public display. [15][18] Beyond ritual, art may have served as a form of communication, a means of documenting events, sharing knowledge about animal behavior, or even marking territories. [14][19] The very act of creating complex symbolic representations, whether figurative or abstract, signifies a crucial evolutionary leap in human cognition. It demonstrates the capacity for abstract thought, imagination, and the ability to externalize complex ideas, which is intimately linked to the development of language and advanced social structures. [15][20] Early art was not just about depicting the world, but about understanding it, interpreting it, and transmitting that understanding across generations, making it a cornerstone of human cultural and intellectual development. [19][21]

Preservation, Modern Challenges, and Enduring LegacyDespite their remarkable endurance over millennia, rock art sites worldwide face increasing threats, both natural and anthropogenic, necessitating urgent preservation efforts. Natural degradation, including weathering, erosion, mineral accretions, and the destructive actions of bacteria and lichen, constantly imperils these fragile artworks. [22][23] However, human impact poses an equally, if not greater, challenge. Development pressures, vandalism, and graffiti directly destroy or deface sites. [22][24] Perhaps the most insidious threat comes from tourism. While public access fosters appreciation, the presence of visitors can drastically alter the delicate microclimates within caves, leading to irreversible damage. The warmth, carbon dioxide from breathing, and introduction of foreign microorganisms can trigger the growth of fungi and mold, as famously occurred at Lascaux. [25][26]

Lascaux, discovered in 1940, had to be closed to the public in 1963 due to visible damage from thousands of daily visitors, with fungi and lichen infesting the walls. [26][27] Subsequent attempts to manage the cave's environment have faced ongoing challenges, including new fungal outbreaks. [25][28] To mitigate such damage, many significant sites now severely restrict access or offer meticulously crafted replicas, like Lascaux II and Chauvet 2, allowing the public to experience the art without harming the originals. [26][29] Climate change further exacerbates natural degradation, with changing environmental conditions accelerating the deterioration of some sites, such as those in Indonesia. [23] The preservation of rock art demands a multi-faceted approach, integrating scientific research, strict site management, community involvement, and robust legal protections. [30][31] These ancient expressions are not merely archaeological curiosities; they are irreplaceable records of our shared human heritage, offering profound insights into the origins of our creativity, spirituality, and intelligence, and their safeguarding is a collective responsibility for future generations.