Biogeochemical Cycles (Carbon, Nitrogen, Water, Phosphorus).

Biogeochemical cycles are the Earth's fundamental life support systems, orchestrating the continuous movement and transformation of matter between living organisms and the non-living environment. These intricate pathways, involving elements like carbon, nitrogen, water, and phosphorus, are not merely isolated processes but are deeply interconnected, forming a complex web that regulates planetary climate, sustains biodiversity, and ensures the availability of essential nutrients for all life. Disruptions to any one cycle can cascade through the entire Earth system, highlighting the delicate balance upon which ecosystem health and human well-being depend. Understanding these cycles is paramount to addressing the profound environmental challenges humanity faces today. [1][2]

The Water Cycle: Earth's Lifeblood in MotionThe water cycle, or hydrologic cycle, is the ceaseless journey of water on, above, and below the Earth's surface, powered by solar energy. It is the primary mechanism for distributing heat and moisture globally, shaping landscapes through erosion and weathering, and, most critically, replenishing freshwater resources vital for all biological processes. Beyond the basic processes of evaporation, condensation, and precipitation, the water cycle involves complex energy dynamics. Evaporation, particularly from vast ocean surfaces, absorbs tremendous amounts of solar energy as latent heat, which is then released back into the atmosphere during condensation, influencing global weather patterns and temperature regulation. [3]

Terrestrial ecosystems play a profound role; for instance, the Amazon rainforest acts as a colossal pump, with its billions of trees drawing water from the soil and releasing vast quantities of moisture into the atmosphere through evapotranspiration. This moisture contributes significantly to regional rainfall, and its influence extends globally, affecting weather patterns as far as Texas, Europe, and China. [4][5] However, human activities are profoundly altering this delicate balance. Deforestation in the Amazon, for example, reduces evapotranspiration, leading to decreased local rainfall and increased drought frequency, potentially pushing the ecosystem towards a tipping point where vast areas could transition to grasslands. [4][6] Furthermore, climate change intensifies the water cycle, leading to more extreme weather events. A warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor (approximately 7% more for every 1°C rise), resulting in more intense precipitation events and, paradoxically, more severe droughts due to increased evaporation from land. This intensification manifests as worsening floods, rising sea levels, and prolonged droughts, impacting freshwater availability and causing immense economic and social disruption, as evidenced by the $550 billion in damages and 40 million displacements caused by water-related disasters in 2024 alone. [3][7] Human interventions like dam construction, extensive irrigation, and groundwater extraction further strain the cycle. The depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains of the United States, a critical source for agriculture, exemplifies this. Over-pumping for irrigation has led to significant water level declines, with some areas experiencing drops of over 40 feet, threatening agricultural output and the viability of rural communities that depend on it. [8][9]

The Carbon Cycle: Earth's Thermostat and Life's FoundationThe carbon cycle is the biogeochemical engine that governs the movement of carbon through Earth's major reservoirs: the atmosphere, oceans, land, and sediments. Carbon, the backbone of all organic life, also acts as Earth's primary thermostat through its atmospheric concentration as carbon dioxide (CO2). This cycle operates on both rapid biological timescales and much slower geological timescales. The fast cycle involves photosynthesis, where plants convert atmospheric CO2 into organic compounds, and respiration, where organisms release CO2 back into the atmosphere. The oceans play a crucial role, absorbing vast amounts of CO2, which then dissolves and forms carbonic acid, bicarbonate, and carbonate ions, supporting marine life and acting as a significant carbon sink. [1][10]

The slow geological cycle involves the burial of organic matter over millions of years, forming fossil fuels and sedimentary rocks like limestone, effectively sequestering carbon. However, human activities have drastically accelerated the release of this geologically stored carbon. The burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas) for energy and industrial processes, coupled with widespread deforestation, releases billions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually. This anthropogenic input has led to atmospheric CO2 concentrations unprecedented in millions of years, driving global warming. A critical feedback loop is the thawing of permafrost in the Arctic, which stores an estimated 1,460-1,600 billion metric tons of organic carbon—twice the amount currently in the atmosphere. [11][12] As permafrost thaws due to rising temperatures, microbes decompose this ancient organic matter, releasing potent greenhouse gases like CO2 and methane (CH4) into the atmosphere, further accelerating warming in a dangerous feedback loop. [11][12] Methane, though shorter-lived, has a global warming potential significantly higher than CO2 over a 20-year period. [13] Beyond atmospheric warming, the increased oceanic absorption of CO2 leads to ocean acidification, lowering the pH of seawater. This directly impacts marine organisms that rely on calcium carbonate to build shells and skeletons, such as corals, oysters, clams, and pteropods, threatening marine food webs and economically vital fisheries. [10][14]

The Nitrogen Cycle: A Double-Edged Sword of Fertility and PollutionNitrogen is an indispensable element for life, forming the structural basis of proteins, nucleic acids, and ATP. Despite making up about 78% of the atmosphere as inert nitrogen gas (N2), most organisms cannot directly utilize it in this form. The nitrogen cycle involves a series of microbial transformations that convert atmospheric N2 into reactive forms usable by plants, and then back again. Nitrogen fixation, primarily carried out by specialized bacteria, converts N2 into ammonia (NH3) or ammonium (NH4+). This is followed by nitrification, where bacteria convert ammonium to nitrites (NO2-) and then to nitrates (NO3-), the primary form absorbed by plants. Assimilation incorporates these forms into organic molecules, and ammonification returns nitrogen to the soil from decaying organic matter. Finally, denitrification completes the cycle by converting nitrates back to gaseous N2, returning it to the atmosphere.

The Haber-Bosch process, an industrial marvel developed in the early 20th century, revolutionized agriculture by artificially fixing atmospheric nitrogen to produce synthetic fertilizers. This process, while credited with feeding billions by vastly increasing crop yields, consumes significant energy, primarily from fossil fuels, and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, including nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas. [15][16] The environmental consequences of this human intervention are profound. The overuse of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers leads to substantial runoff into aquatic ecosystems. This excess nitrogen acts as a nutrient pollutant, triggering massive algal blooms (eutrophication) in freshwater bodies and coastal zones. When these algae die and decompose, they deplete dissolved oxygen, creating vast hypoxic "dead zones" where marine life cannot survive. A stark example is the recurring dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, largely fueled by agricultural runoff from the Mississippi River basin, which impacts fisheries and biodiversity. [17][18] Beyond eutrophication, excess reactive nitrogen contributes to acid rain, ground-level ozone pollution, and the release of N2O, which is approximately 300 times more potent than CO2 as a greenhouse gas over a 100-year period and also depletes the stratospheric ozone layer. [15][16]

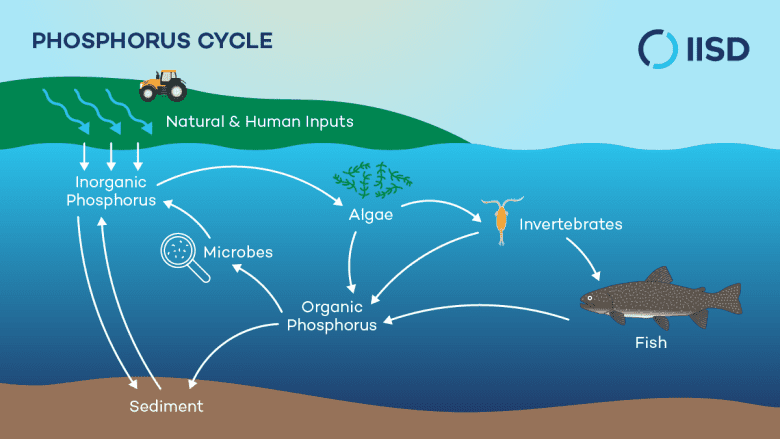

The Phosphorus Cycle: The Limiting Nutrient's Slow JourneyThe phosphorus cycle is unique among the major biogeochemical cycles due to its lack of a significant atmospheric gaseous phase. Phosphorus, primarily found in solid form within rocks and sediments, is a critical component of DNA, RNA, ATP, and cell membranes, making it indispensable for all life. Often, it is the most limiting nutrient in many ecosystems, particularly aquatic ones. The cycle begins with the slow weathering of phosphate-rich rocks, which releases dissolved inorganic phosphate (PO43-) into soils and water. Plants absorb this phosphate, and it then moves through food webs as organisms consume one another. Upon death or waste excretion, decomposers return organic phosphorus to the soil or water, where it is converted back into inorganic forms. Over geological timescales, phosphorus can settle in aquatic environments, forming new sedimentary rocks, which may then be uplifted to restart the cycle. [19]ity's impact on the phosphorus cycle is dominated by the mining of phosphate rock for agricultural fertilizers. This finite resource is essential for maintaining global food production, but projections suggest that readily available supplies could be depleted within decades, leading to a phenomenon known as "peak phosphorus." [19][20] The inefficient use of phosphorus in agriculture, where often only 15-30% of applied fertilizer reaches crops, exacerbates this scarcity. [21] Similar to nitrogen, excess phosphorus from agricultural runoff and wastewater discharge is a major contributor to eutrophication in lakes, rivers, and coastal areas. This nutrient overload fuels harmful algal blooms, depletes oxygen, and devastates aquatic ecosystems, impacting drinking water quality and fisheries, as seen in instances like the algal blooms in Lake Erie. [17][22] Sustainable phosphorus management strategies are urgently needed, focusing on improving fertilizer use efficiency through soil testing and precise application, recycling phosphorus from wastewater and organic wastes, and developing crop varieties that are more efficient at phosphorus uptake. [21][23]

In conclusion, the biogeochemical cycles of water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus are the fundamental pillars supporting Earth's habitability. Their intricate interactions regulate climate, provide essential nutrients, and maintain the delicate balance of ecosystems. However, human activities, driven by industrialization, agriculture, and population growth, have profoundly disrupted these cycles, leading to global warming, ocean acidification, widespread pollution, and resource depletion. Recognizing the interconnectedness of these cycles and the severe consequences of their imbalance is the first step towards fostering a sustainable relationship with our planet. Urgent, integrated, and intelligent management strategies are required to restore balance, mitigate environmental damage, and ensure the long-term health and resilience of Earth's life-sustaining systems for future generations.